It doesn’t have to be a rat rod…

By Daniel Strohl, Hemmings Motor News

I am not building a rat rod. Sure, at first mention of my Model A highboy pickup project, it may seem as though I’ve jumped on the latest bandwagon to roll through Koolsville along with the rest of the swing-dance-and-pomade neo-rockabilly set.

Rough paint, solid axles front and rear, and parts cribbed from a variety of makes, models, and years of automobile. Even parts cribbed from the discount bins at Home Depot. When finished, the pickup should be about as far from the billet-independent-front-suspension-and-ostrich-skin-interior street rod look so popular today.

But it still won’t be a rat rod.

Modern hot rodding occupies a variety of territories, many of which border on and overlap each other. The human tendency to picture topics in black and white or to effectively compartmentalize everything falls short here, though it seems kinda easy at first.

You’ve got the street rods, where modern technology and convenience underpin decades-old styling. Don’t want to deal with finding a lifter for a flathead Ford V-8 when broken down in the middle of Kansas? Don’t want to try to find an all-steel Deuce three-window? Then throw a small-block Chevrolet V-8 into a fiberglass shell and be done with it. And that’s fine for some people. Prime example: Most of the cars built by Boyd Coddington’s shop in the television show American Hot Rod.

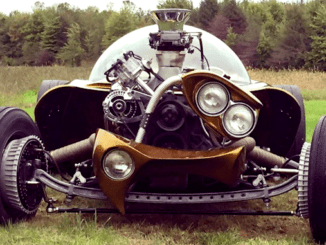

You’ve got the rat rods, where technology, convenience and safety are more often thrown out the window than celebrated. Or even concerned about. Rat rodders cite the lack of a budget and the return to the roots of hot rodding as their main motivations, but the dictums of fashion more often provide their impetus.

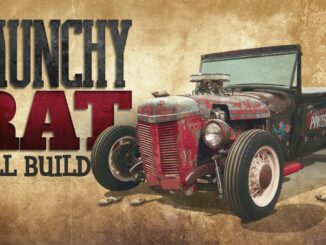

Major hot-rodding organizations, which had previously spurned rat rodders from their ranks, have recently taken a shine to the immensely marketable trend and begun allowing the cars into their shows. And lately, rat rod builders seem to be challenging each other to build the most outrageous examples of the breed, with snake-belly stances, midget-only chop-and-channel jobs and interiors decked out completely in tiki-styled bamboo. And that’s fine for some people. Prime example: Mark Idzardi’s Purple People Eater.

You’ve got traditional rods, where attempts to replicate what the pioneers of hot rodding built in the 1940s and 1950s seem to get lost in what’s correct and what’s not. Even if traditional rodders aren’t building a clone of a certain historical hot rod, many simply pick a year in the 1940s or 1950s and refuse to install any piece that wasn’t available before that year. But in the quest for historical accuracy, builders of traditional rods forget that early hot rodders built their cars in just as many styles as today’s hot rodders do. And that’s fine for some people. Prime example: Mike Bishop and Vern Tardel’s Model A V-8 roadster.

And then there are the rest of us. We’re either bored with fashion or simply don’t care. We’re as likely to take inspiration from Art Chrisman and Ralph Schenck as we are from the cars that populate our daily drives. Maybe we just have ideas that don’t fit in the above categories, but still fall under the general banner of hot rodding. Maybe we’re actually on a budget, but would rather have floorboards in our rides and the peace of mind in a quality build job. Maybe we appreciate the styling and simplicity of the pioneer hot rods, but think that we can do a little better with a few modern components. Maybe we’d like to be comfortable in our hot rods, but don’t care for flash or gadgetry. Maybe we just don’t care about the latest show-stopping trend, and we just don’t need a formula.

I actually began collecting parts for this project a couple of years ago. Back then, I wanted a lakes modified roadster, something along the lines of Nick Conti’s T modified-built without a huge pile of cash and with the inspiration of the cars that ran on the dry lakes before streamliners replaced them in the late 1940s. I picked up parts here and there-a grille and radiator from a 1930 Pontiac at a swap meet for $30, an early 1960s Falcon steering column and box at a swap meet for $3, a mid-1980s Chevrolet pickup four-speed and 1948 Ford pickup rear axle from a buddy as a trade for a couple of Astro vans.

But, as projects occasionally evolve, so did this one. After moving to Vermont, I realized that I’d be able to drive an open car just a few months of the year. Not good, because without a garage of my own, I plan on enjoying this car as much as possible. And I’ve always been fond of pickups. When I came across a picture of a closed-cab 1929 Model A highboy pickup, chopped a modest amount, painted flat black, sitting fairly high, wearing no fenders or hood and powered by a hot Model A four-cylinder engine, the hamster wheel in my head started frantically spinning. I took the picture into Photoshop, tweaked it a bit, and knew exactly what I wanted to do. I didn’t actually have a closed-cab pickup body, but I’ll worry about those details later.

The real catalyst came when I bought a Model A frame and cowl from another buddy on Long Island for $300. He told me the frame had been used for several years as a fence post for a chicken coop. The crusty duct tape peeling off it leads me to believe so. I later traded him a crusty 1957 Pontiac that I got for free in exchange for a front axle, rear spring and a spare rear axle, along with split front and rear wishbones.

One of the more entertaining aspects of the parts collection effort so far has been the process of seeking out the Model A enthusiasts who have what I need. I’ve found guys as near as New Hampshire and as far away as California willing to help me once they see that I’m young and genuinely interested in the cars. Sure, I occasionally run into the restorers who wouldn’t sell a thing to a hot rodder, but I use it as a prime opportunity to show them that these parts were headed for the scrap heap or long decades of dust-collecting duty had I not come along.

For example, I found a fella selling three Model A engines-all crusty and requiring a dunk in a molasses bath-for $150. Two were sitting in an abandoned barn and one was lying in a patch of weeds. Definitely not going to win points at Hershey. He threw in a bucketload of other parts that he no longer needs and introduced me to a friend of his who has a barn full of Model A parts that he hasn’t touched in probably 20 years. A neighbor of his, who had a yard full of doodlebugs and a pile of perhaps 20 engines under a blue tarp, sold me a complete front axle for $40.

My cash outlay so far: $606. Add in the value of all the parts I’ve swapped, subtract the value of the extraneous parts I’ll be able to sell off (fenders, running boards, etc.), and this project still should have a total value of somewhere south of $1,500.

It helps to have a vision for this project. I intend to meet three goals with this pickup: To perform as much of the work myself as possible, to keep the total cost of the project low, and to have a daily driveable pickup when I’m finished. Note I made no mention of time; with those goals and a steep learning curve ahead of me, it has paid to develop patience for this project.

Parts sources will be about as diverse as the parts I intend to use. Junkyards seem an obvious proposition for the modern components; scamming deals from my buddies and cohorts, who have been collecting cast-off parts for much longer than I have, will constitute another good majority. I don’t believe many restorers or street rodders would have anything to do with any piece of this pickup, from the sheer patina and abuse the parts have collected over the years. I cringe at the idea of turning to new parts catalogs because of the expense, but am slowly coming to realize that this project won’t wrap up anytime soon if I stick to a pre-1960-only philosophy.

Notice also that I made no mention of paint. On the priority list, driving the pickup ranks just under upholstery and well above shiny stuff.

The one area in which I know I’ll end up spending more money than expected will be the engine. Real hot rods are so only because of their engines, so a stock Model A four-cylinder just won’t cut it. Of course, the quick, dirty and cheap answer would be a small-block Chevrolet V-8, but it’s also the answer everyone else offers. So I’m thinking insert bearings, a full-pressure oiling system and an overhead-valve conversion on a Model A block will qualify as a hot rod engine. The adapter to use that engine in front of a synchronized transmission won’t be cheap, either.

But if I scrimp, save, barter, beg and finagle everywhere else on this project, then-theoretically-I should have a few extra dinero to spend on the engine.

The important thing, though, is that I enjoy this project, not only when it’s finished, but also at moments like these, scanning through Hemmings, meeting other enthusiasts willing to help get a project off the ground, or striking deals with buddies, looking for just the right parts for just the right bargain. That’s what hot rodding, at its core, has been about nearly since the beginning and I imagine what it will continue to be like for years to come.

And maybe, once I finish this hot rod, I’ll be able to get around to building that modified.