Three guys you’ve probably never heard of recently broke a speed record most people don’t care about—the New York to Los Angeles run referred to colloquially among aficionados as the Cannonball.

Unlike most speed records and races, there’s no sanctioning body or official rules. That’s because setting a Cannonball record invariably involves breaking multiple traffic laws. In other words, it’s illegal. But that doesn’t stop people from doing it.

You may or may not be aware of its existence, but there’s a robust subculture within the automotive enthusiast community that obsesses over the New York-to-L.A. land speed record. Many of them even go so far as to race beater cars coast to coast every year (also against the law) in most-holds-barred Cannonball-style races called the 2904 and the C2C Express.

Two members of the informal “fraternity of lunatics,” as it calls itself, are Arne Toman and Doug Tabbutt, who—along with a new-to-the-mania young spotter named Berkeley Chadwick—are the latest Cannonball champions.

At least two dozen attempts are known to have been made by others since the last record was set in 2013, but only one managed to break 30 hours. Toman, Tabbutt and Chadwick succeeded not just in breaking a record many people thought would be difficult or impossible to break. They utterly destroyed it, making the trip in less than 27 and a half hours.

But that’s the nature of records. When they’re broken, the people who care cheer, sigh, curse, start drinking or whatever, then mutter something to the effect of, “Oh, nobody’s gonna ever beat that.” And then someone does.

That’s what people said when David Diem and Doug Turner set a 32-hour, 7-minute record in 1983, and again when Alex Roy and Dave Maher raised the bar to 31 hours and 4 minutes in 2006. No-can-do was definitely the tone when Ed Bolian and Dave Black screamed across the country in 28 hours and 50 minutes in 2013, a record that stood until now.

ut the latest team to achieve the seemingly impossible has introduced a time that Brock Yates could never even have imagined when he dreamed up the Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash almost 50 years ago. However, it was Yates’ New York-to-L.A. race/party on wheels that planted the seeds of an automotive counterculture that has come to revere his legacy with cult-like fervor and pay it homage by driving incredibly fast.

“I didn’t want to break the record by minutes,” Toman said. “I didn’t want anyone else trying and I didn’t want to do it again.”

After leaving the Red Ball Garage on the east side of Manhattan at 12:57 a.m. on November 10, it took Toman, Tabbutt and Chadwick 27 hours and 25 minutes to reach the Portofino Hotel in Redondo Beach, in L.A.’s South Bay. In a car.

If number crunching isn’t your thing, allow me to break that down for you:

Taking the northern route—I-80 through Nebraska, I-76 down to Denver, I-70 to the middle of Utah and I-15 down into L.A.’s spiderweb of interstates for a total of 2825 miles—Toman and Tabbutt were able to maintain an overall average speed of 103 mph. That’s including stops for fuel, which they managed to keep down to a blindingly fast 22 and a half minutes total. And that’s in a country where the speed limit on interstate highways is usually 70 mph, and never higher than 80 on the roads they were traveling.

Well before they hit the road in Toman’s souped-up all-wheel-drive 2015 Mercedes-Benz E63 AMG sedan, bristling with electronics, Toman and Tabbutt were already deep into their mission, Chadwick being a recent addition who happened to be a good spotter. For the most part, the run was Toman and Tabbutt’s baby.

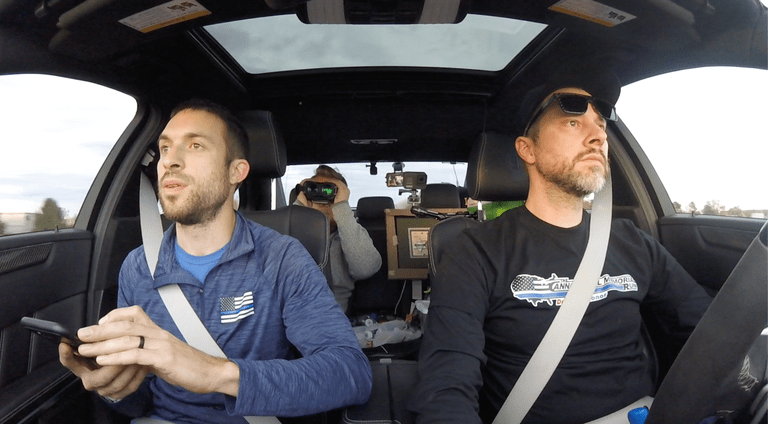

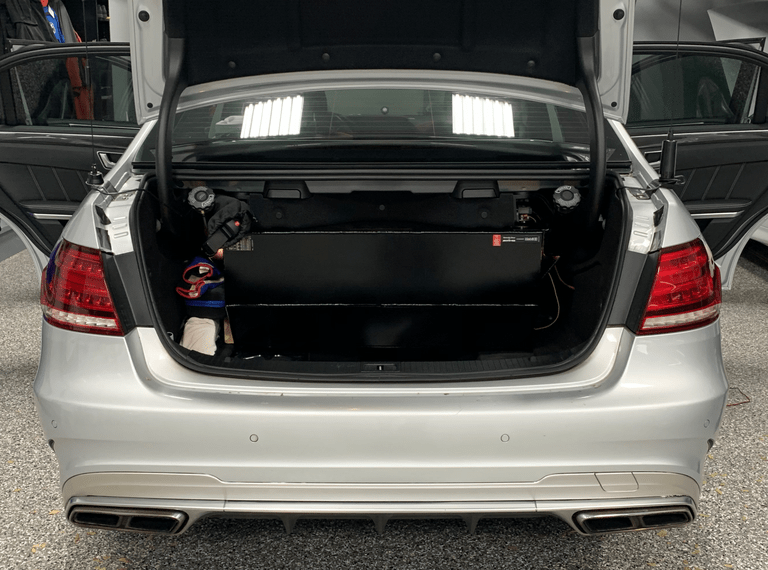

They were the ones obsessed with beating Bolian’s record, and they spent hundreds of hours planning and preparing, with Toman responsible for getting the car built and kitted out with a custom-fabricated fuel cell and an arsenal of electronic counter-measures and Tabbutt handling logistics and information. They shared driving duties once they hit the road, and recruited Chadwick to man the gyro-stabilized binoculars and keep a sharp lookout for police.

The plain Jane-looking silver AMG sedan was custom-built for the record attempt, and not just by being fast. Sure, it puts down about 700 horsepower to the wheels (according to Toman), thanks to an ALPHA 9 package with upgraded turbos, downpipes, intercoolers and intake (the brakes and suspension are all factory AMG stuff and work just fine at any speed).

But there was also a built-in Net Radar radar detector, a windshield-mount Escort Max 360 radar detector, an AL Priority laser jammer system and an aircraft collision avoidance system—a bit of gear usually used in airplanes to help them avoid hitting other airplanes. In this case, the technology was meant to help the trio find highway patrol aircraft.

The car was equipped with brake light and taillight kill switches, and Toman had all of its flashy carbon fiber trim covered with silver vinyl, which he also used to change the appearance of the taillights. At first glance, the AMG looked more like a mid-2000s Honda Accord from the rear, not like a car that would be cruising at 160 mph or faster.

For navigation and further police detection, they ran Waze—a popular traffic-avoiding and hazard-detecting app—on an iPad and an iPhone. For the GPS data they would later need to prove that they’d actually finished in the time they said they did, they ran two dash-mount Garmin GPS units and one of those GPS tags tracked by a third party. They also had a police scanner and a CB radio, each of which had a big whip antenna mounted at the back of the car.

“Probably the most trick thing I had was a thermal scope on a roof-mounted gimbal that could be operated via remote control by the back seat passenger,” Toman said, explaining that although it was great for seeing deer, they removed the large black device from the car during daylight hours to avoid attracting attention. “We picked up a cop warning on Waze and we were able to see the heat signature of the car sitting on the side of the road.”

But there were limitations to all that gear. The car, which had been superbly prepared, began running poorly somewhere in the Rockies, where a combination of high altitude and low-octane gasoline caused detonation. (Toman stopped the car and shut off the engine, and fortunately for them, it started back up and ran normally after that.) The aircraft tracker didn’t find anything because there just weren’t any patrol aircraft flying. They found that if the thermal scope was turned too far in one direction, it would get stuck there, the gimbal motors unable to overcome the force of the wind. The police scanner only worked in places that hadn’t yet switched over to encrypted digital communications, and the CB was more or less worthless.

“Doug was absolutely hell-bent on having a CB, so I humored him,” Toman said. (For anyone who grew up watching Burt Reynolds banter with truckers in Cannonball Run and Smokey and the Bandit, citizens band is a dyed-in-the-wool tradition, after all.)

What really made the difference between previous record runs and theirs, though, was the human component. The team had a lot of help from their extensive network of car nerd friends and business associates. Toman is the co-founder AMS Performance, and although he no longer works there, he still knows a lot of performance car enthusiasts and Gumball 3000 devotees. Tabbutt, founder and owner of Switchcars, sells used performance and exotic cars for a living and knows all sorts of people who would much rather be driving fast than doing anything else, if not supporting other people who are driving fast.

“There were a lot of phone calls where I’d say, ‘Hey how’s that car I sold you three years ago? By the way, what are the cops like where you are?'” Tabbutt said. “There’s no replacement for boots on the ground and we had lots of information from people everywhere—stuff you can’t get from the Internet.”

In all, they managed to rustle up 18 lookouts along the run. These were people who drove hundreds of miles in many cases just to scout the road ahead of the fast-moving AMG for a stretch and let the team know of any police activity or other hazards ahead. Carl Reese, a one-time holder of the coast-to-coast motorcycle speed record who also set an autonomous-car record with Roy, guided them through part of California on his BMW motorcycle.

“Having that many spotters is something we all would have dreamt of,” Bolian said. “Their greatest success was in inspiring that many people to go out in the middle of the night, drive into the middle of nowhere, and help them beat something everyone said was impossible.”

There was also a healthy helping of good luck involved in the run. Toman said they didn’t have any close calls in terms of accidents, but they did manage to avoid possible jail time at one point. Somewhere in the Midwest, they missed spotting a police car headed in the opposite direction until it was right on top of them. The officer driving the cruiser must have noticed they were going faster than the rest of the traffic and lit them up with instant-on radar, which gave them no time to slow down.

At that point, Toman and Tabbutt said the car was hurtling down the Interstate at about 120 mph, although they declined to specify who was behind the wheel at the time. They scanned to the rear and waited for the inevitable brake lights and turn around, which never came. Minutes later, they called one of their lookouts, who was at a filling station nearby, watching the same black Ford Explorer patrol vehicle get gassed up by a police officer. The lookout overheard radio chatter that may have pertained to the AMG.

Then Toman, Tabbutt and Chadwick passed a police car setting up a speed trap on the median a few miles ahead, but the officer behind the wheel didn’t take notice of them. The ubiquitous-silver-sedan disguise had worked, and the rest of the trip passed without further incident where law enforcement was concerned.

When all is said and done, there will be three kinds of reactions to an achievement of this kind.

One will be outright indignation that anyone would endanger public safety by traveling at such speeds. That’s to say nothing of the wives and parents—including Tabbutt’s—who don’t tend to like it when their loved ones put themselves in harm’s way in service of so frivolous a pursuit. This response is not without merit. Although Cannonball drivers, including Toman and Tabbutt, claim to be hyper-focused and safe while driving two to three times the posted speed limit, the US ain’t Germany, where the left lane on the Autobahn is kept clear for the fastest drivers.

To date, no one has been killed or seriously injured doing a Cannonball or setting a cross-country record in the U.S., but American motorists don’t expect such high speeds, and truckers usually resent it. There’s potential for disaster.

“In America, we have allowed ourselves to believe that we cannot be good drivers,” Roy said. “But in Germany, people hit speeds faster than Arne’s average Cannonball speed just driving home from work on the Autobahn.”

The other responses will be from another crowd—Cannonballers and motorheads of all stripes who believe that driving skill, and not traffic law, is more beneficial to actual safety than simply slowing down. From this side of the aisle, there will be unadulterated joy that such a cross-country time has been posted, as well as begrudging appreciation from former record holders and disappointed fanatics who may have been planning record runs of their own.

Toman, who had toyed with the idea of trying to break the record since hearing about Roy’s record in 2007, recalled being crushed when he found out about Bolian’s 28:50 time a few years later. He didn’t think he could beat it.

“You have to start and end always with the idea that all records can be broken,” Roy said, drawing a parallel between setting a Cannonball record and Roger Bannister’s success in knocking down the 4-minute barrier in the mile run. “If you work backwards from there, anything’s possible.”

Within the context of automotive achievements, Cannonballing has a long history, and the continuity from one generation to the next is as inevitable as it is palpable. Modern Cannonballers tend to revere Yates and other characters from the raucous events he organized in the ’70s, but even Yates studied those who came before him as he tried to understand the best way to push those boundaries.

The record he broke in 1971 had been set by Erwin “Cannonball” Baker, and had stood since 1933. And it all just sort of cascaded down from there. Records were set every few years during the ’70s, then came Diem and Turner and all the rest of their more serious and secretive US Express cohort, who based their runs upon the exploits of the ’70s Cannonballers. Then Roy, Bolian, and now Toman and Tabbutt, scrutinized the advances that had been made by all the crazies who came before them. Bolian—who introduced Toman and Tabbutt to one another and who has driven with Toman in a couple of Cannonball races—posits that his efforts to expand the Cannonball community may have had something to do with their success. (His record certainly seems to have ignited renewed fervor around Cannonballing. He estimates that since 2015, more than 100 runs have been made in the 2904 and C2C Express.)

Tabbutt offered a matter-of-fact observation about his relationship with the longstanding record-holder.

“Don’t just meet your heroes, beat your heroes,” he said.

It’s difficult to imagine that anyone will best 27:25 anytime soon, but who knows. The reasons people give for the impossibility of such a feat sound suspiciously like Brock Yates’ contention, decades ago, that American roads were too crowded and police-infested for anyone ever to beat the record set during the last Yates-era Cannonball race in 1979. It only took a few years for someone to prove him wrong. Now we find ourselves looking at the victorious claimants of a dizzying new record—an Everest of sorts. Was it a good idea? No. It never has been and it never will be. But like Everest, it presents itself as a risky challenge that is, to some, irresistible.

From: Road & Track

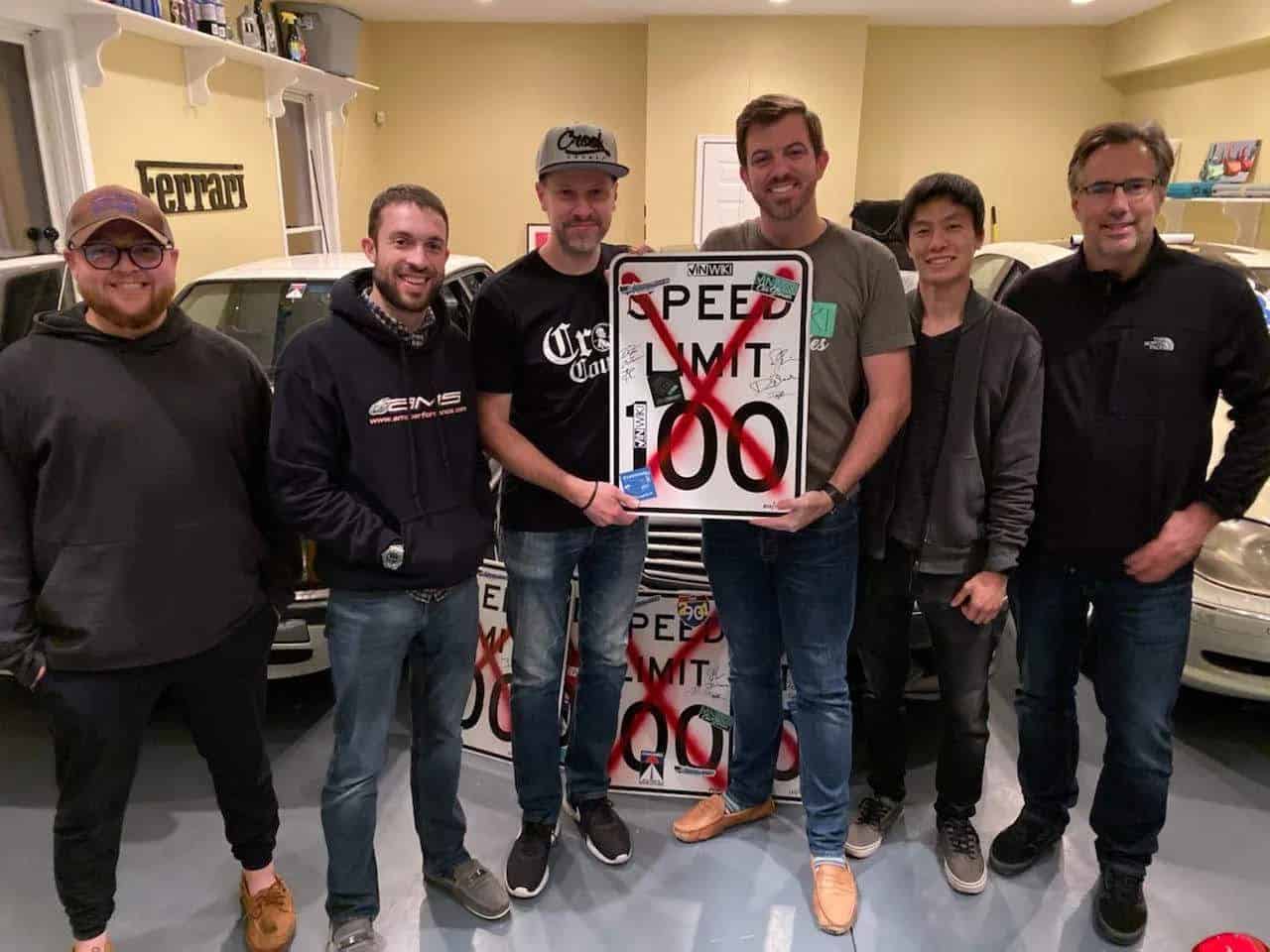

Cannonball Run Record 100MPH Signs

VINwiki has 100 vandalized speed limit signs signed by Arne’s team and Ed’s team available in our store with the profits supporting Cannonball Memorial Run and the Brock Yates Tribute Fund. SOLD OUT.